07.05.2024

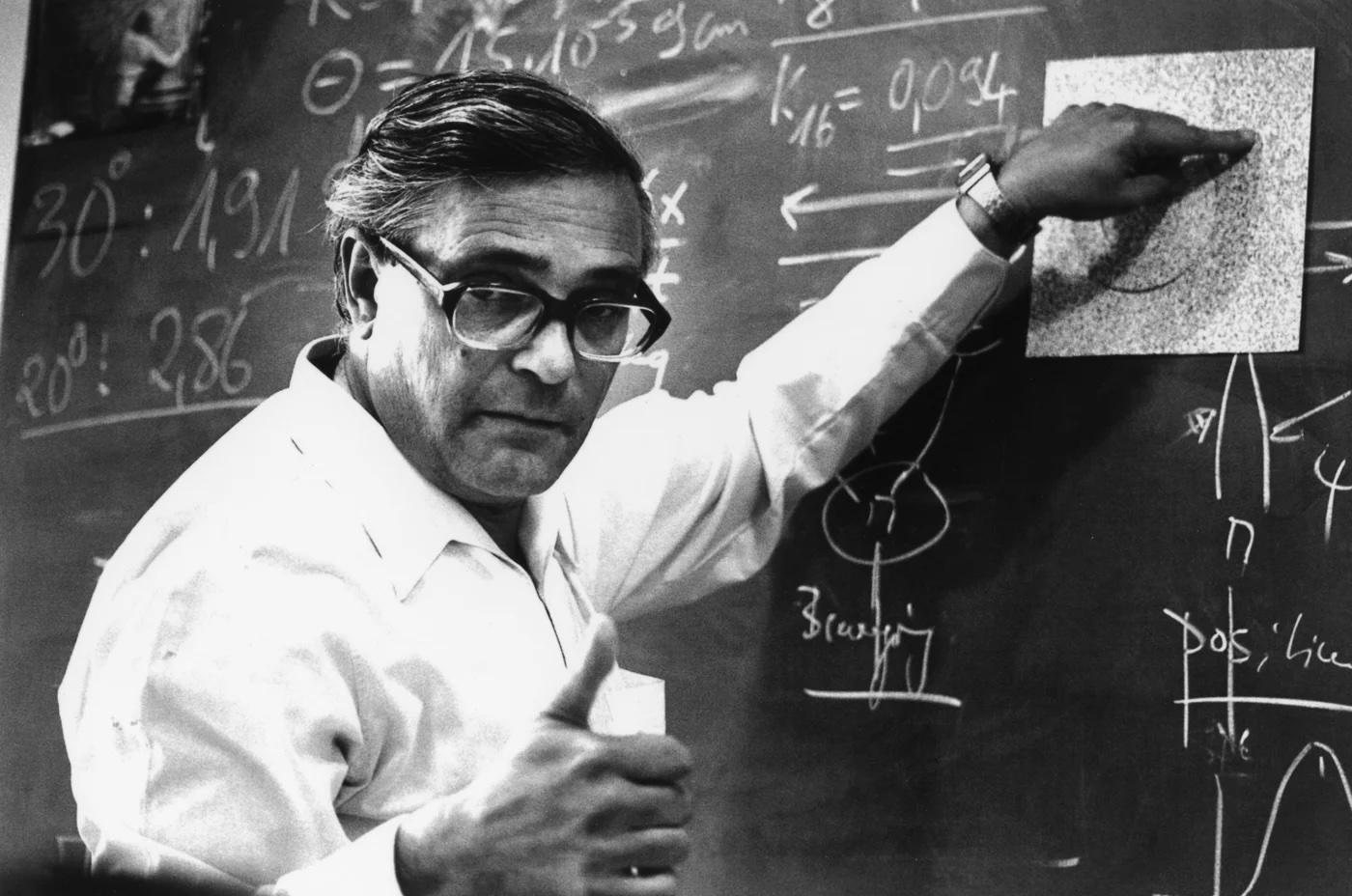

Werner E. Reichardt 100th birthday - a memorial to a great Tübingen neuroscientist

On 24 January this year, Werner E. Reichardt, founder of the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics and namesake of the university's interdisciplinary Werner Reichardt Centre for Integrative Neuroscience, would have turned 100 years old. To mark the return of this birthday, a symposium was held at the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics on 19 April 2024, which succeeded in conveying Reichardt's enduring importance through a successful mixture of reminiscent, sometimes very personal contributions to Reichardt and reports on current research in the footsteps of Reichardt.

Reichardt's research topic was the investigation of the orientation behaviour of insects. He saw it as a practical model system for the attempt to gain insight into the fundamental principles of information processing in biological organisms. Of course, Reichardt was not the first person to be interested in the behavioural control of insects and their dependence on vision and other sensory systems. But what set him apart from many others in his time and before him was his conviction that biological organisms should be understood primarily as information-processing systems. This was a view that grew out of the thinking of the information, communication and control sciences - "cybernetics" - that blossomed around the Second World War.

He saw the precise quantitative description of behaviour and its successful mathematical modelling as an indispensable prerequisite for trying to understand how a biological organism could perform the functions of interest. Based on well-founded models and the predictions they make, it would be possible to pursue the question of how sensory and nerve cells and their connections in networks make the model's performance possible at subordinate levels of analysis. It was this concept of the necessary interlocking of hierarchical levels of analysis that became the founding manifesto of the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics and was realised over many years in successful and internationally influential work at this institute and by partners at the university.

Reichardt's "level concept", which was later popularised by David Marr, stands in clear contrast to reductionist approaches in the neurosciences. They consider it sufficient to decipher elementary genetic, molecular and cellular principles, the combination of which, like a mosaic, would then make it possible to understand the biological basis of complex brain functions. This approach was bound to fail. Rather, fundamental understanding requires - as Reichardt demanded - an equal approach at different levels of analysis, from information processing using the toolbox of theory - now traded under the heading of "computational neuroscience" - to that of the genome.

Reichardt could hardly have imagined that his old institute, which nowadays seems almost tranquil and small, would one day become part of the exploding science and technology park of the "Obere Viehweide" - a location on a hill that is now amusingly known as "Cyber Valley". And the concept of intelligence, which is the centre of attention in Cyber Valley today, probably did not play a significant role in Reichardt's thinking either. But when we discuss today that intelligence as the result of information processing in machines is possibly indistinguishable from the result of information processing in the human brain - in other words, that there could be artificial intelligence that is indistinguishable from biological intelligence - then we are engaging in a discussion that was undoubtedly inherent in Reichardt's thinking.

Incidentally, the fact that Reichardt was able to exert this eminent influence on scientific developments is due to the fortunate coincidence that, against all probability, he survived the horrors of Nazi rule. Reichardt was drafted into a radio unit of the Wehrmacht immediately after graduating from high school in 1941 because of his knowledge of physics and technology. However, after he later made radio contact with the "enemy", he was arrested by the Gestapo in 1944. He was only able to avoid the threat of execution by luckily escaping and going into hiding in Berlin until the end of the war.

We at the Werner Reichardt Centre for Integrative Neuroscience at the University of Tübingen's Schnarrenberg have tried to commemorate the enduring importance of this Tübingen scientist for modern neuroscience by choosing his name for our centre. But should not we perhaps do more to keep alive the memory of someone whose internationally recognised life's work is closely associated with the scientific city of Tübingen? If you look at the streets in the area of Tübingen's science centres, you will notice that some of them bear the names of scientists who were undoubtedly important, but who have hardly any relevant biographical links to the city. Perhaps it would be time to reconsider some of the names and to name a street after a Tübingen scientist who stood out and was a pioneer in the development of a location-specific profile for neuroscience.

Peter Thier, Senior Professor of Cognitive Neurology at the Hertie Institute for Clinical Brain Research and founding spokesperson of the Werner Reichardt Centre for Integrative Neuroscience at the University of Tübingen