Press Releases Archive

16.09.2024

The herbivorous panda was not always so

Team at the University of Tübingen’s Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment finds omnivorous ancestor of the giant panda – two new studies published

The Hammerschmiede fossil site in southern Germany has yielded finds from about 11.5 million years ago which have rewritten evolutionary history. The sole species of bear discovered to date at the site was a relative of the giant panda. Its diet, however, more closely resembled the mixed diet of today’s brown bears. An international research team from Hamburg, Frankfurt, Madrid and Valencia headed by Professor Madelaine Böhme from the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment at the University of Tübingen discovered this in their study of the dietary and life habits of 28 species of predator from the Hammerschmiede that have since died out. Two publications on the investigation of these finds have appeared in Papers in Palaeontology and Geobios.

The Hammerschmiede became famous in 2019 following the discovery there of the earliest, roughly 11.5 million-year-old great ape that was adapted to walking upright, Danuvius guggenmosi. The latest excavations led by Madelaine Böhme at the site brought to light an extraordinary variety of 166 fossilized species. “Such a flourishing ecosystem offers a wealth of ecological niches for the species that live in it,” says Böhme. Many of the animals lived both in the water and on the land, or could climb trees. “This meant they could adapt to the forested river landscape which was in the region at that time,” says Böhme.

What the teeth reveal

The only bear species in the Hammerschmiede – called Kretzoiarctos beatrix – is regarded as the oldest ancestor of the modern giant panda, since the form and composition of its teeth have similarities to those of pandas, which eat almost nothing but bamboo. Kretzoiarctos beatrix was smaller than modern brown bears, but weighed more than 100 kilograms. “Today’s giant pandas are part of the group of carnivores in the zoological taxonomy, but in fact, they live exclusively on plants. They’ve specialized in a hard vegetable diet, specifically of bamboo,” reports Dr. Nikolaos Kargopoulos from the University of Tübingen and University of Cape Town, the lead author of the new studies. It is scientifically interesting how these pandas – who were originally carnivores – adapted to such an extreme herbivorous diet, Kargopoulos added.

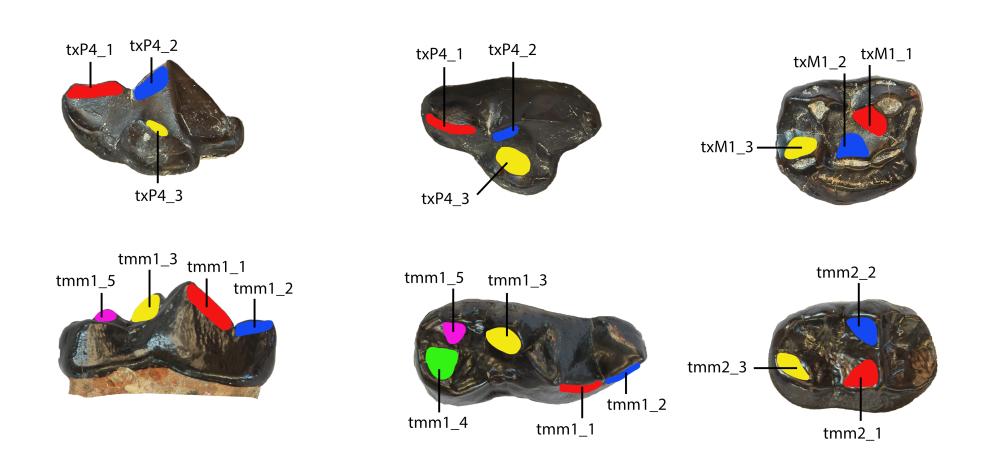

In a first study, the research team investigated the diet of Kretzoiarctos using the macro- and micromorphology of found teeth. At the macro level, the form of the teeth changes depending on their role in processing food, which gives an indication of an animal’s general primary sources of food. At the micro level of the dental surface, scratches and pits can be found that are caused by food particle contact with the tooth. “The characteristics of these surface changes can give clues to the dietary habits of an animal in a short period before its death,” says the scientist.

The research team compared the macro- and micromorphology of the Kretzoiarctos teeth with those of brown bears, polar bears, South American spectacled bears and both the giant pandas of today and extinct giant pandas. They concluded that the bear from Hammerschmiede did not specialize in hard plants like the modern panda, but nor was it a pure carnivore like the polar bear. The diet of the extinct species was more like that of a modern brown bear and contained both plant and animal elements. “These results are important to our understanding of the evolution of bears and the development of herbivory in giant pandas. It turns out that Kretzoiarctos beatrix, the oldest of the pandas was a generalist. Specialization in the panda’s diet only came about late in its evolution,” says Böhme.

The diversity of predators from the Hammerschmiede

Besides the panda, a further 27 species of predator have been found at the Hammerschmiede, the researchers report in a second study. The predators range from tiny, weasel-like animals that weighed less than a kilogram, right up to large hyaenas and saber-tooth tigers that weighed more than 100 kilograms. “Their respective primary sources of food were very varied: there were pure carnivores such as the saber-tooth tiger, fish-eaters like the otter, and bone-eaters such as the hyaena. A few other species like the panda and the marten fed opportunistically on plants and animals of various sizes,” Kargopoulos says. These new species were also very different in their choice of habitat: “The otter-like animals were good swimmers; bears, hyaenas and others stayed on the land or lived in burrows like the skunks. A strikingly large number of species were tree-climbers like the marten, cat-like animals, genets and red pandas,” explains Kargopoulos.

“Such a diverse population of predators is not only extremely rare in fossil terms; there’s hardly any modern habitat with a similarly large number of species,” says Böhme. This diversity of species at the top of the food chain indicates that the ecosystem of the Hammerschmiede must have worked extremely well. In fact, there are even species that thrived side-by-side, even though they occupied very similar niches, the researcher says. “For example, there are four different otter-like animals of approximately the same size and type of diet. Normally, they would compete for the natural resources in their environment. But it seems that the resources of the Hammerschmiede were rich enough to meet the needs of every species.”

Publications:

Nikolaos Kargopoulos, Juan Abella, Alexander Daasch, Thomas Kaise, Panagiotis Kampouridis, Thomas Lechner, Madelaine Böhme: The primitive giant panda Kretzoiarctos beatrix (Ursidae, Carnivora) from the hominid locality of Hammerschmiede: dietary implications. Papers in Palaeontology, https://doi.org/10.1002/spp2.1588

Nikolaos Kargopoulos, Alberto Valenciano, Juan Abella, Michael Morlo, George E. Konidaris, Panagiotis Kampouridis, Thomas Lechner, Madelaine Böhme: The carnivoran guilds from the Late Miocene hominid locality of Hammerschmiede (Bavaria, Germany). Geobios, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geobios.2024.02.003

Hammerschmiede

In a clay pit near Pforzen in the southern German Allgäu region, the University of Tübingen and the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment have been conducting excavations headed by Professor Madelaine Böhme since 2011. Since 2017 there has been a citizen science project involving locals in the work, and since 2020 the team has received funding from the state of Bavaria. About 40,000 fossils from 150 species of vertebrates have so far been found, including the two great apes Danuvius guggenmosi and Buronius manfredschmidi.

Contact:

Dr. Nikolaos Kargopoulos

University of Tübingen / University of Cape Town

+ 30 69 80 17 01 72

nikoskargopoulosspam prevention@gmail.com

Prof. Dr. Madelaine Böhme

University of Tübingen

Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment

+ 49 7071 29-73191

m.boehmespam prevention@ifg.uni-tuebingen.de

Contact for press:

Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen

Public Relations Department

Christfried Dornis

Director

Janna Eberhardt

Research Reporter

Telefon +49 7071 29-77853

Fax +49 7071 29-5566

janna.eberhardtspam prevention@uni-tuebingen.de

All press releases by the University of Tübingen