attempto online

12.10.2023

Neanderthals hunted dangerous cave lions and used their pelts

For the first time, a new study by an international research team shows Neanderthals hunted cave lions and used the pelt of this dangerous carnivore

Excavations at Einhornhöhle (Unicorn Cave) in the Harz Mountains (Lower Saxony, Germany) in 2019 uncovered abundant Ice Age fauna, among which were a few bones of the extinct cave lion. The bones were discovered in a cave gallery approximately 30 meters from the now-collapsed entrance in a layer older than 200,000 years. The bones have now been investigated by researchers from the Lower Saxony State Office for Cultural Heritage and the Universities of Tübingen and Reading. While analyzing the finds, Gabriele Russo from the Institute for Archaeological Sciences of the University of Tübingen detected a toe bone (phalanx) with a cut mark, which only makes sense if the animal was skinned to yield a pelt with the claws still attached. Such behavior shows that Neanderthals valued the lion pelt.

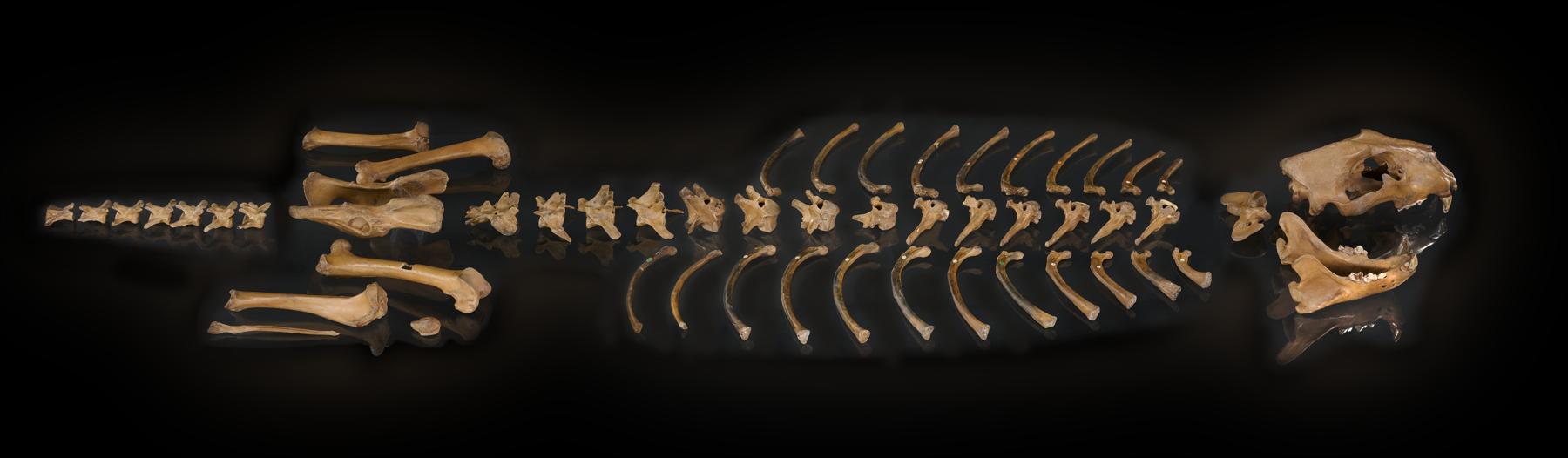

Yet the bones found at Einhornhöhle did not provide any direct evidence for hunting. In order to contextualize the finding, Russo analyzed further cave lion remains and made an exciting discovery. In 1975 a teenager from Siegsdorf in Bavaria (Germany) found the well-preserved remains of a cave lion. A closer inspection by Russo of that skeleton confirmed many cut marks and led to the detection of some unusual damage on a rib. Working with archaeologist Annemieke Milks from the University of Reading, Russo identified the damage as a weapon impact. “The rib lesion clearly differs from the bite marks of carnivores and shows the typical breakage pattern of a lesion caused by a hunting weapon,” says Russo. According to Milks, “The lion was probably killed by a spear that was thrust into its abdomen when it was already lying on the ground.” For the first time this around 50,000-year-old skeleton proves that Neanderthals hunted cave lions. The cut marks also show that not only did they kill this apex predator, they also consumed its meat.

The cave lion had a shoulder height of around 1.3 meters and was the most dangerous animal in Eurasia during the 200,000 years before it went extinct at the end of the Ice Age. Cave lions lived in various environments from the steppe to the mountains and, as top predator, they hunted large herbivores such as mammoth, bison and horse, as well as cave bear. They are called cave lions because their bones are often found in Ice Age caves.

It was long believed that cave lions were not hunted until the advent of Homo sapiens. Among Homo sapiens’ earliest artworks are those found in caves of the Swabian Jura in southwestern Germany. There the cave lion is a prominent motif, exemplified by the famous lion man figurine made of ivory and dated to around 40,000 years ago. Cave lions also feature in rock art panels in Grotte Chauvet in south-eastern France, which are about 34,000 years old.

Basis for later cultural developments

The new results demonstrate that cave lions also held special meaning for Neanderthals. Thomas Terberger from the Lower Saxony heritage authority, speaker of the project “Climate Change and Early Humans in the North,” says: “The human desire to gain respect and power via a lion trophy is rooted in Neanderthal behavior; the lion is a powerful symbol of rulers right up to the present day.”

The new study contributes to the growing picture of behavioral similarities between Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens. Recently, an engraved giant deer bone from Einhornhöhle illustrated the ability of Neanderthals to produce and communicate with symbols. The role of cave lions fits with the evidence of more complex Neanderthal behaviors, and could even have laid the basis for later cultural developments by Homo sapiens.

The study has been published in the journal Scientific Reports. It was financially supported by the Lower Saxony Ministry of Science and Culture within the project “Climate Change and Early Humans in the North” (www.ccehn.de).

Publication:

G. Russo/ A. Milks/ D. Leder/ T. Koddenberg/ B.M. Starkovich/ M. Duval/ J.-X. Zhao/ R. Darga/ W. Rosendahl/ T. Terberger: First direct evidence of lion hunting and the early use of a lion pelt by Neanderthals. Scientific Reports 2023, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42764-0

Contact:

Gabriele Russo

University of Tübingen

Institute for Archaeological Sciences

gabriele.russospam prevention@uni-tuebingen.de

Dr. Dirk Leder/ Prof. Dr. Thomas Terberger

Lower Saxony State Office for Cultural Heritage

Scharnhorststrasse 1, 30175 Hannover

Dirk.Lederspam prevention@NLD.Niedersachsen.de

Thomas.Terbergerspam prevention@NLD.Niedersachsen.de

Dr. Annemieke Milks

University of Reading

a.g.milksspam prevention@reading.ac.uk

Dr. Robert Darga

Museum Siegsdorf

robert.dargaspam prevention@museum-siegsdorf.de

Contact for press:

Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen

Public Relations Department

Dr. Karl Guido Rijkhoek

Director

Janna Eberhardt

Research Reporter

Telefon +49 7071 29-77853

Fax +49 7071 29-5566

janna.eberhardtspam prevention@uni-tuebingen.de

All press releases by the University of Tübingen

Back