Press Releases Archive

15.08.2018

Seeing on the Quick: New Insights into Active Vision in the Brain

Tübingen neuroscientists expand on role of superior colliculus – disregarded area in brainstem processes visual stimuli on its own

Eye movements are controlled by a small, centrally located area in the brainstem, the superior colliculus (“small upper hill”). A team of neuroscientists at the University of Tübingen headed by Prof Z. Hafed (Werner Reichardt Centre for Integrative Neuroscience – CIN/Hertie Institute for Clinical Brain Research – HIH) has recently found clear evidence that this brain area not only controls eye movements, but also processes visual input on its own. This brain area processes coarse image regions common to our natural environment especially quickly, and therefore facilitates efficient orienting behaviour in real-world situations.

“The way that the superior colliculus processes visual input from our surroundings is specifically tuned to what we need to efficiently orient ourselves”, Prof Ziad M. Hafed introduces his object of study. The leader of a research team at the CIN and HIH has been investigating the primate visual system for years. In primates – and thus in us humans –, conscious seeing is primarily jumpstarted in the visual cortex, a well-known area of the cerebral cortex. But based on their own earlier studies, Hafed’s research group was convinced that the “small upper hill” in the brainstem maintains very important visual functions as well. For instance, it plays a paramount role in the visual system of fish and amphibians. In mammals and especially in primates, however, this brain area has been thought to mostly just control eye movements and attention.

But Hafed and his team are convinced that the superior colliculus plays a central role in visually-driven environmental orientation and navigation as a whole. “If a brain area controls eye movements, then it seems intuitive that it also fulfills important functions in general orienting behaviour”, Hafed puts it, adding: “But to do so, it must also be able to process visual information.”

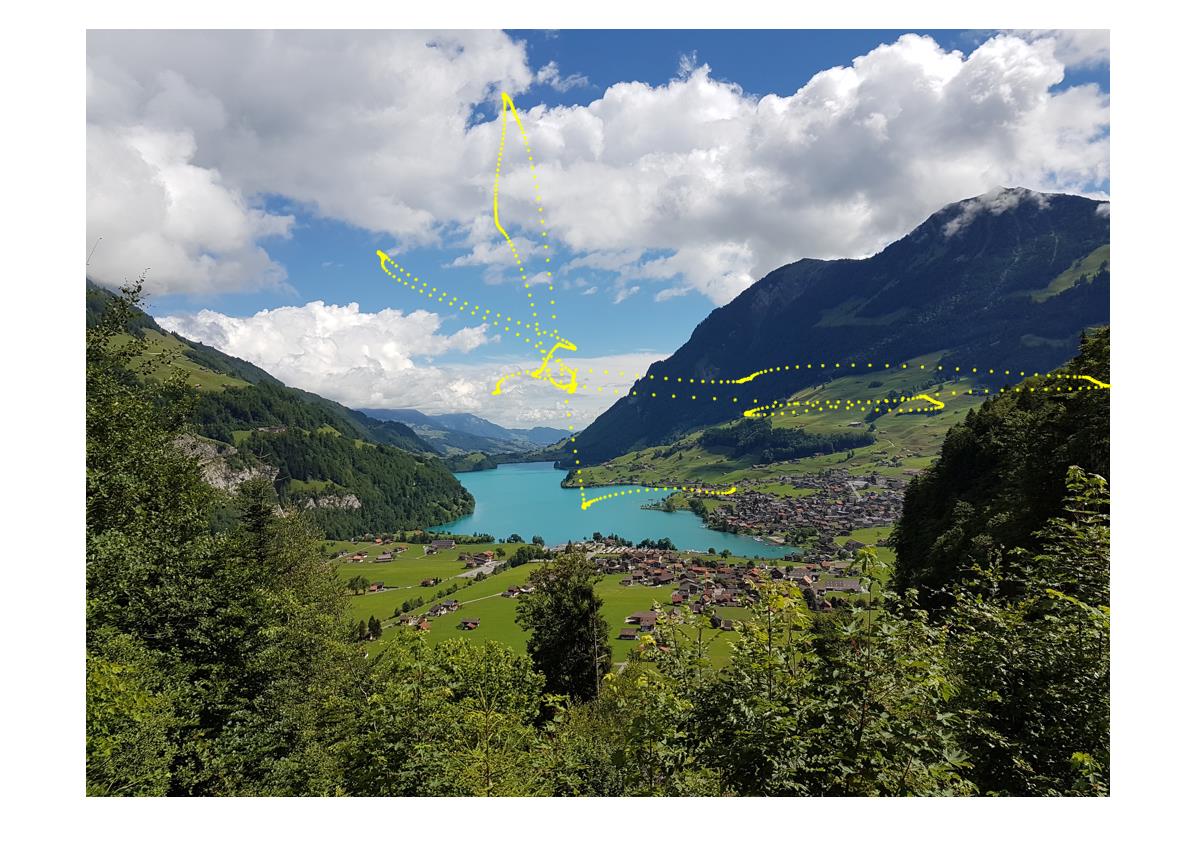

To investigate this hypothesis, the Hafed lab performed neurophysiological experiments with rhesus macaques, whose visual system is very similar to our own. The researchers investigated how individual brain cells (neurons) responded to different visual stimuli. Would changes in features such as the image’s orientation, its contrast and background, and other image properties make a difference in how superior colliculus neurons responded? If this area is responsible for spatial orien-tation, neurons here must respond especially quickly to those stimuli towards which we would need to direct our attention first. In natural environments, our attention is primarily focused on the most general features first: is there an open space in front of us, are there obstacles, is there a figure or a face? In order for us to cope with our surroundings, our brain must process such features as quickly as possible; fine details can wait for closer inspection.

For this reason, the researchers observed how the neurons they were investigating responded to coarse image features with low amounts of variation in visual information – or (as the scientists call it) with low spatial frequency. This might be the case with large swathes of forest or sky or clouds in our surroundings. The result: neurons in the superior colliculus do in fact respond to visual stimuli with low spatial frequency the quickest. Naturally, the observed set of neurons did not all respond identically, some going so far as to show a stronger overall response to high spatial frequency stim-uli. But even these high-frequency specialists still responded more quickly to the presentation of coarse image patches: the “turbo boosting” of neural responses to low-frequency stimuli took priority over actually sensing the image content itself. This is important, as the turbo-boosted signal was also instrumental in determining how efficiently eye movements are made.

Thus, the “little hill” in our brain has the ability to analyse visual patterns – a capability most scientists would have denied this brain area could have. “We have added evidence that the primate superior colliculus is not merely an organ of motor control,” says Hafed, “but a visual structure that may be just as important as the primary visual cortex in allowing us to function in our everyday surround-ings.”

Publications:

Chen, C. -Y., Sonnenberg, L., Weller, S., Witschel, T., & Hafed, Z. M. (2018). Spatial frequency sensitivity in macaque midbrain. Nature Communications, 9: 2852.

doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05302-5.

Chen, C. -Y. & Hafed, Z. M. (2018). Orientation and contrast tuning properties and temporal flicker fusion characteristics of primate superior colliculus neurons. Frontiers in Neural Circuits (Special Research Topic on The Superior Colliculus/Tectum: Cell Types, Circuits, Computations, Behaviors), 12:58.

doi: 10.3389/fncir.2018.00058.

Contact the Author:

Prof. Dr. Ziad M. Hafed

Werner Reichardt Centre for Integrative Neuroscience (CIN)

Otfried-Müller-Str. 25

72076 Tübingen

Germany

Phone: +49 (0)7071 29-88819

ziad.m.hafed@cin.uni-tuebingen.de

The University of Tübingen

Innovative. Interdisciplinary. International. Since 1477. These have always been the University of Tübingen’s guiding principles in research and teaching. With its long tradition, Tübingen is one of Germany’s most respected universities. Tübingen’s Neuroscience Excellence Cluster, Empirical Education Research Graduate School and institutional strategy are backed by the German government’s Excellence Initiative, making Tübingen one of eleven German universities with the title of excellence. Tübingen is also home to five Collaborative Research Centers, participates in six Transregional Collaborative Research Centers, and hosts six Graduate Schools.

Our core research areas include: integrative neuroscience, clinical imaging, translational immunology and cancer research, microbiology and infection research, biochemistry and pharmaceuticals research, the molecular biology of plants, geo-environment research, astro- and elementary particle physics, quantum physics and nanotechnology, archeology and prehistory, history, religion and culture, language and cognition, media and education research.

The excellence of our research provides optimal conditions for students and academics from all over the world. Nearly 28,000 students are currently enrolled at the University of Tübingen. As a comprehensive research University, we offer more than 250 subjects. Our courses combine teaching and research, promoting a deeper understanding of the material while encouraging students to share their own knowledge and ideas. This philosophy gives Tübingen students strength and confidence in their fields and a solid foundation for interdisciplinary research.

The Werner Reichardt Centre for Integrative Neuroscience (CIN)

The Werner Reichardt Centre for Integrative Neuroscience (CIN) is an interdisciplinary institution at the University of Tübingen funded by the DFG’s German Excellence Initiative program. Its aim is to deepen our understanding of how the brain generates functions and how brain diseases impair them, guided by the conviction that any progress in understanding can only be achieved through an integrative approach spanning multiple levels of organization

.

The Hertie Institute for Clinical Brain Research (HIH)

Founded in 2001, the Hertie Institute for Clinical Brain Research (HIH) was brought to life by an agreement between several entities: the non-profit Hertie Foundation, the State of Baden-Württemberg, the University of Tübingen and its Medical Faculty, and the University Hospital of Tübingen. The HIH deals with one of the most fascinating fields of today´s research: the decoding of the human brain. The main question is how certain diseases affect brain functions. In its daily work, the HIH builds the bridge from basic research to clinical application. Its goal is to facilitate new and more effective strategies for diagnosis, therapy and prevention. At present, the HIH is home to a total of 21 professors and about 380 employees.

Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen

Public Relations Department

Dr. Karl Guido Rijkhoek

Director

Antje Karbe

Press Officer

Phone +49 7071 29-76789

Fax +49 7071 29-5566

antje.karbe[at]uni-tuebingen.de

www.uni-tuebingen.de/en/university/news-and-publications.html